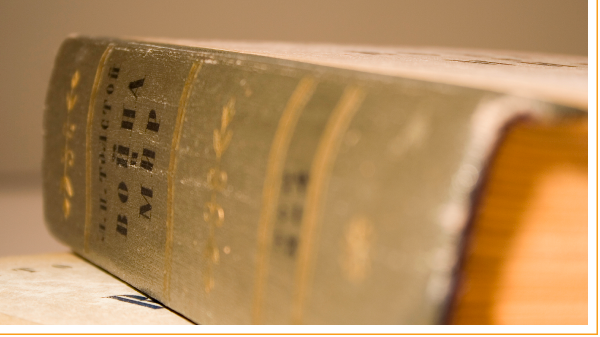

Let’s start with the question: how does Leo Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace” end? What is the last word of this novel? This is how the second part of the Epilogue ends: “to recognize a dependence of which we are not conscious” (Translators: Louise and Aylmer Maude, 2001)

Let’s start with the question: how does Leo Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace” end? What is the last word of this novel? This is how the second part of the Epilogue ends: “to recognize a dependence of which we are not conscious” (Translators: Louise and Aylmer Maude, 2001)

The last word in the text of the four-volume novel “War and Peace” in Russian is ‘zavisimost’, ‘dependence’. This is perhaps the key word for the entire artistic world of Leo Tolstoy, where even the greatest historical personality does nothing on his/her own, but on the contrary, is connected by countless threads with other people who need to be heard, seen and felt.

If the first question was, perhaps, complicated, we do not read War and Peace every day, then the second question should be simple. What words end the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible? This is the famous decree of Cyrus the Great:

“Thus says Cyrus, king of Persia. All the kingdoms of the earth have been given to me by the Eternal One, the God of Heaven. And He commanded me to build a Temple for Him in Jerusalem, in Judea. Those who belong to His people – may their God be with them! — let them go there” (Chronicles 2, 36:23)

In Hebrew, the last word is VE-YAAL, literally: “one may go up.”

The completion of the books of Divrei ha-Yamim, the Chronicle, and therefore the entire Hebrew Bible, is the decree of King Cyrus, who allowed the Jews to return to their land. This decree meant the end of the Babylonian Exile, and was seen by the prophets as a sign that the Eternal One had changed anger to mercy. The last sentence of the entire Hebrew Bible is in many ways reminiscent of the final verses of the Torah (Pentateuch): the Jews are about enter the Promised Land. At the end of the Chronicles, the people of Israel are again on the threshold of their country, which has yet to be found. Thus, the entire Hebrew Bible shows (even by its composition, the arrangement of books) that the land of Israel is a place where the Jews have yet to come. The path is not over yet, the “golden age” is not in the past, but in the future.

But what will happen to those who do not want, or for some reason will not be able to “ascend” to the Land of Israel? We know from history that not all Jews returned from Babylon. Those who do not return are not lost to Jewish history at all. They will create a diaspora in historical Babylon. This Diaspora will leave us the famous Talmud as a legacy, and a little later it will produce what we still use today – the siddur, the calendar, the Passover Haggadah in its current form, the halakhic codes, the literature of the Responsa genre (She’elot u-Teshuvot). And here our “dependence” is manifested – we depend on the heritage of Babylon, its Gaons, both in the Diaspora or in the Land of Israel.

The weekly portion of Matot-Masei ends the narrative of the entire Pentateuch. The people of Israel are on the threshold of the Promised Land, the crossing of the Jordan is about to take place. There remains, of course, the fifth book of the Torah, Dvarim (Deuteronomy), but it does not contain new events, only the farewell of Moses and his final instructions. The last events take place in our current Torah passage.

Not all Jews now standing on the threshold of the Promised Land will enter there. And it’s not just Moses. Chapter 32 of the book of Bemidbar tells that several tribes of the people of Israel ask Moses to leave them beyond the Jordan. Moses is initially angry, we can easily understand his first reaction: he himself dreamed of ascending to the Promised Land, but he was not given this, and suddenly someone voluntarily (!) refuses this. But then Moses makes an informed decision. And this is his last decision, one might say “the last decree”, what constitutes the legacy of any ruler. And in this “decree” he allows to live outside of the future land of Israel. Thus, the “birth of the Diaspora” takes place. This can be used as a classic example of a win-win situation: those who wish to settle on the other side of the Jordan River will receive good pastures, and those tribes of the people of Israel who settle inside the Promised Land will receive larger plots of land. In addition, those who will live beyond the Jordan play an important role: for example, they will be the first to be hit by foreign invaders. And here we have dependence again – all the tribes of Israel depend on each other.

Moses, with his “last decree” outlined the direction in which Judaism should move: to be a religion that takes into account the opinions and interests of everyone, and this will ultimately turn out to be good for everyone. Such an open, non-dogmatic religion, which obliges us to hear and listen to others, was left to us by Moses, and thanks to this dependence on each other, we have existed for several thousand years.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ).

The last word in the text of the four-volume novel “War and Peace” in Russian is ‘zavisimost’, ‘dependence’. This is perhaps the key word for the entire artistic world of Leo Tolstoy, where even the greatest historical personality does nothing on his/her own, but on the contrary, is connected by countless threads with other people who need to be heard, seen and felt.

If the first question was, perhaps, complicated, we do not read War and Peace every day, then the second question should be simple. What words end the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible? This is the famous decree of Cyrus the Great:

“Thus says Cyrus, king of Persia. All the kingdoms of the earth have been given to me by the Eternal One, the God of Heaven. And He commanded me to build a Temple for Him in Jerusalem, in Judea. Those who belong to His people – may their God be with them! — let them go there” (Chronicles 2, 36:23)

In Hebrew, the last word is VE-YAAL, literally: “one may go up.”

The completion of the books of Divrei ha-Yamim, the Chronicle, and therefore the entire Hebrew Bible, is the decree of King Cyrus, who allowed the Jews to return to their land. This decree meant the end of the Babylonian Exile, and was seen by the prophets as a sign that the Eternal One had changed anger to mercy. The last sentence of the entire Hebrew Bible is in many ways reminiscent of the final verses of the Torah (Pentateuch): the Jews are about enter the Promised Land. At the end of the Chronicles, the people of Israel are again on the threshold of their country, which has yet to be found. Thus, the entire Hebrew Bible shows (even by its composition, the arrangement of books) that the land of Israel is a place where the Jews have yet to come. The path is not over yet, the “golden age” is not in the past, but in the future.

But what will happen to those who do not want, or for some reason will not be able to “ascend” to the Land of Israel? We know from history that not all Jews returned from Babylon. Those who do not return are not lost to Jewish history at all. They will create a diaspora in historical Babylon. This Diaspora will leave us the famous Talmud as a legacy, and a little later it will produce what we still use today – the siddur, the calendar, the Passover Haggadah in its current form, the halakhic codes, the literature of the Responsa genre (She’elot u-Teshuvot). And here our “dependence” is manifested – we depend on the heritage of Babylon, its Gaons, both in the Diaspora or in the Land of Israel.

The weekly portion of Matot-Masei ends the narrative of the entire Pentateuch. The people of Israel are on the threshold of the Promised Land, the crossing of the Jordan is about to take place. There remains, of course, the fifth book of the Torah, Dvarim (Deuteronomy), but it does not contain new events, only the farewell of Moses and his final instructions. The last events take place in our current Torah passage.

Not all Jews now standing on the threshold of the Promised Land will enter there. And it’s not just Moses. Chapter 32 of the book of Bemidbar tells that several tribes of the people of Israel ask Moses to leave them beyond the Jordan. Moses is initially angry, we can easily understand his first reaction: he himself dreamed of ascending to the Promised Land, but he was not given this, and suddenly someone voluntarily (!) refuses this. But then Moses makes an informed decision. And this is his last decision, one might say “the last decree”, what constitutes the legacy of any ruler. And in this “decree” he allows to live outside of the future land of Israel. Thus, the “birth of the Diaspora” takes place. This can be used as a classic example of a win-win situation: those who wish to settle on the other side of the Jordan River will receive good pastures, and those tribes of the people of Israel who settle inside the Promised Land will receive larger plots of land. In addition, those who will live beyond the Jordan play an important role: for example, they will be the first to be hit by foreign invaders. And here we have dependence again – all the tribes of Israel depend on each other.

Moses, with his “last decree” outlined the direction in which Judaism should move: to be a religion that takes into account the opinions and interests of everyone, and this will ultimately turn out to be good for everyone. Such an open, non-dogmatic religion, which obliges us to hear and listen to others, was left to us by Moses, and thanks to this dependence on each other, we have existed for several thousand years.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ).