Our Torah portion this week (דברים) may have the most innocuous name of any – it can be translated as “words” or “things”. The root ד.ב.ר. appears through the Tanach and if you read from the Torah as a Bar or Bat Mitzvah you may recall a verse beginning וידבר ה’ אל … or something similar, indicating God actually speaking. Jewish tradition has a strong oral component, not only in the form of Biblical and halachic commentary (think Mishna and Gemara) but even within the texts themselves.

Our Torah portion this week (דברים) may have the most innocuous name of any – it can be translated as “words” or “things”. The root ד.ב.ר. appears through the Tanach and if you read from the Torah as a Bar or Bat Mitzvah you may recall a verse beginning וידבר ה’ אל … or something similar, indicating God actually speaking. Jewish tradition has a strong oral component, not only in the form of Biblical and halachic commentary (think Mishna and Gemara) but even within the texts themselves.

Let’s look at the Ten Commandments for example – in Hebrew they are known simply as עשרת הדברות, the ten utterances. They are often, but not always, represented by letters on two arched tablets (In Hebrew individual letters have numeric value so 1= א) In other words, pardon the pun, before they were etched into stone, the paragraph we term the Ten Commandments was spoken by God to Moses. What we have then, is a transcript of divine speech to humans. That’s a funny word itself – trans (between) script (writing) – and here is where I come to the heart of the matter in looking at this week’s Torah portion: the space between the speaking of the words and the written record we have of them now.

On the surface Deuteronomy (did I mention the Latin name for this book means second word or copy?) is a recap, a summary, a retelling of the Torah up until Moses’ death and Joshua’s leadership begins. The first time I learned that the Five Books of Moses were not all edited by the same hand I was confused. We call them the Five Books of Moses so they must share the characteristic of having been transcribed by him, no? In an Orthodox perspective this is true – the Torah was dictated to Moses by God at Mount Sinai. From my perspective as a Reform Jew, the historicity of that event is less important to me. I still feel the immediacy of that moment as I sit in my house in the Arava desert of Israel only kilometers away from where some of the events recorded in last week’s portion took place. The struggle is of course, to make sense of both the text and modern life. The book of Numbers ends with the instruction to enter the land, expel all its inhabitants, portion it into areas for the tribes and to settle the land forever. Which, as plans for conquest go, was pretty standard for the ancient world. Again, from one perspective this is permission to have hegemony in the land. As a modern person, I’m not sure that’s the point. Here we are this week, poised as it were, to take possession of what we understand to be rightfully ours. The “action” takes place in what is now southern Israel (near Kibbutz Lotan) but what was then outside the boundaries of the land of Israel, but that’s another story…

The first chapter of this capstone, this summary of what has gone before, sets the stage physically and emotionally for what follows. We are a people on the brink! We’re about to enter the land of Israel. But you know, there are some things, some דברים to be spoken of first. And who is doing the speaking? This time it’s Moses: “These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel…” (Deut 1:1) “It was in the fortieth year, on the first day of the eleventh month…” (Deut. 1:3) so we have the time. But here is the unusual bit, here we have Moses not only telling, or retelling, what God spoke to him, here we have a huge clue to what makes this book so different: “on the other side of the Jordan, in the land of Moab, Moses undertook to expound this Teaching…” (Deut 1:5)

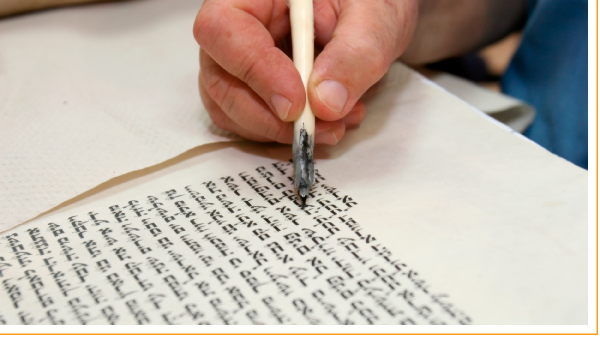

Hold on to your hat! Moses is giving the people of Israel not only God’s instructions but also his interpretation of them?! Has he been doing that all along?? The answer is we’ll never know because while critical literary analysis of the Torah text show clear stylistic and linguistic differences between narratives from Genesis, Exodus and Leviticus for instance, we don’t have any of the first drafts. What we do have are the stories that we told ourselves when we were just one family in Genesis, stories that accompanied us, and perhaps sustained us, as we both grew in numbers and then became slaves in Egypt. What we retain are the memories of our gatherings – to break bread, to celebrate new life, to mourn those who have died, yes, even to give thanks to God. What we have is the final edit, not the first revision or even the thousandth. We have the awareness that shows in Moses’ elucidations. We have stories passed down for millennia that not only changed over time, each of us changed over time. This is Moses after forty years in the desert, Moses who has seen an entire generation complain, be satisfied for a minute and complain again, a man who has seen plagues and attacks cull many from his flock. A man who lost his temper, struck a rock instead of speaking to it and who now knows he will not enter the land. He wants us to understand that what he has seen has taught him that it is not one particular word, not לשמור instead of לזכור that is ultimately significant but the intent behind the words. Our texts are sacred, but we do not encase them in glass and put them on pedestals to be admired. We protect them with precious cloth and carry them into the congregation. We bring them close to us so we may see them as ours.

Each of us hears the story a different way each passing year. We bring our God given intellect and hard-won life experience to the text and we EXPOUND on it. The physical words of the scroll we sincerely attempt to copy faithfully, but the intent behind the words we consistently struggle to unearth. We do not only read the words, we bring our own words to meet them. In synagogue we read first Torah, then what is essentially a commentary on the message of that portion chosen by ancient scholars, i.e. a selection from the Prophets or Writings, known now as Haftara. And then we continue to comment and interpret by hearing a sermon or D’var Torah. What Moses does in the beginning of our Torah portion, what I at least feel he can’t help but do, is bring himself to the words. This is our challenge today as well, to see that our reaction and interaction with the text is an integral part of our tradition. We draw strength from its message – Torah is our Tree of Life.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ).