Rabbi Dr. Rena Arshinoff, PhD | Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

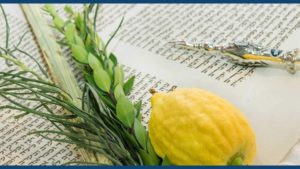

We are commanded to rejoice during Sukkot. The holiday of Sukkot is filled with traditions and symbolism. We partake in dwelling in the sukkah, shaking the four species, giving thanks for the harvest, expressing joy, inviting others, and showing hospitality. While these are very much “hands on” activities, Sukkot is a rather intellectual holiday. It follows the intensely contemplative and reflective days of awe and Yom Kippur in which teshuva is the key theme but even as we rejoice, it is at the same time, filled with paradoxes and striving for balance.

We are commanded to rejoice during Sukkot. The holiday of Sukkot is filled with traditions and symbolism. We partake in dwelling in the sukkah, shaking the four species, giving thanks for the harvest, expressing joy, inviting others, and showing hospitality. While these are very much “hands on” activities, Sukkot is a rather intellectual holiday. It follows the intensely contemplative and reflective days of awe and Yom Kippur in which teshuva is the key theme but even as we rejoice, it is at the same time, filled with paradoxes and striving for balance.

At Sukkot, we offer thanks for the harvest of fresh fruits and vegetables abundant in our wealthy part of the world yet so many people live in areas of famine. Toward the end of Sukkot, we engage in Hoshana Rabba in which we offer prayers for rain and we insert a special prayer in the Amidah for rain. Water is so important for us for life and sustenance of life yet so much of the world suffers from draught. Water is fraught with symbolism – our bodies are 80% water; we are born in water; water is a powerful image in Torah beginning with Creation, the Garden of Eden near the river; the Flood; wells are mentioned many times in Bereshit; the Israelites miraculously cross the Sea of Reeds; Moses and his ability to obtain water from a rock. The mikveh and washing our hands before eating are other symbolic rituals. Yet there are paradoxes: although God did provide water from a rock via Moses, it was exactly this situation that prevented Moses from entering the Promised Land. While the prayer for rain is crucial, rain does have limitations. Rain is needed for crops but too much rain may ruin them. Water sustains us yet wreaks havoc when it is overabundant such as tsunamis, hurricanes, rapids, and high seas can take lives.

At this holiday, we sit in the sukkah, a fragile structure that does not have a sealed roof but shchach, branches laid across the top. We are required to be able to see the stars and moon yet when it rains, it can flood the sukkah and even knock it down. We rejoice as we give thanks for the harvest of our food and for the abundance of what we have even while we know that such abundance is not experienced by all. This holiday commands us to rejoice and be happy yet we are reminded of the fragility of life as symbolized by the frailty of the sukkah. At the same time that we rejoice in God’s gifts, we are also reminded of those who do have such good fortune.

How do we handle such paradoxes? Paradoxes take us out of our comfort zone and cause us to squirm. It is not so easy to praise God for what we have at the same time that we see others suffering from hunger; we praise Creation yet we destroy our environment; we preach about compassion, goodness, and welcoming others but we see wickedness. Sukkot presents us with paradoxes while inviting us to find balance. One of the themes of Sukkot is unity. The four species that we hold together and shake represent an odd kind of ritual but offer the metaphor of unity as they are held together. A midrash about the four species suggest that they represent four types of people representing our diversity that ultimately creates all of humanity; it is from our differences that we learn how we are actually the same. Another midrash teaches that each of the four species represents a different part of our body that together allow us to be whole and to experience God.

Sukkot reminds us that the world is filled with paradoxes and it is up to us to find balance to offset such inconsistencies in our world. But like a tightrope walker, finding balance requires hard work, concentration, and believing we can do it. We are responsible for maintaining the world in a healthy way: to recognize the fragility of life and the fragility of the world that God created through balancing the differences between those of us who “have” and helping to provide for those who “have not”. The Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 27b indicates that all of Israel should dwell in the “same sukkah”. Rabbi Eliezer said this means that one should dwell in the same sukkah for the entire holiday and not move from one to another; another interpretation however, is that all of Israel should dwell in the same sukkah together rather than in separate sukkot; this strong metaphor teaches that by all of Israel sitting together in one sukkah, we will achieve the spiritual message of the holiday, that of unity and recognize the importance of ensuring those less fortunate are invited into our one sukkah.

Just as the shofar on Rosh Hashanah serves as a wakeup call for us to focus on our personal teshuva, the paradoxes we recognize at Sukkot also serve as a wakeup call and beckon to us to engage in teshuva for the world. It is through the messages of Sukkot that we can search for balance to world paradoxes. We have to open our heart to strangers and to the issues of the greater world as we unlock the door to our house or the entrance to our sukkah. The balance of the world depends on us all through our joint effort that will strengthen the earth and the world through unity as we dwell together in the same metaphoric sukkah and truly rejoice at this holiday.

Chag Sameach!

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ).