Rabbi Harry Rosenfeld| Congregation Albert, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Va’etchanan begins with Moses’ lamenting to the people that because of his action of disobeying God at the Waters of Bitterness God punished him by not allowing him to enter the land of Canaan (see Parashat Chukat, Num. 20.) Moses would not see his efforts beginning in Egypt leading the people from slavery to freedom, and through the trials in the wilderness, reach it’s culmination in the restoration of the Israelites to the land of Canaan. In Va’etchanan, Moses does not accept that his actions brought on his punishment. Rather, he blames the Israelites for his punishment. “But the Eternal was angry with me on your account and would not listen to me” (Dt. 3:26)

Va’etchanan begins with Moses’ lamenting to the people that because of his action of disobeying God at the Waters of Bitterness God punished him by not allowing him to enter the land of Canaan (see Parashat Chukat, Num. 20.) Moses would not see his efforts beginning in Egypt leading the people from slavery to freedom, and through the trials in the wilderness, reach it’s culmination in the restoration of the Israelites to the land of Canaan. In Va’etchanan, Moses does not accept that his actions brought on his punishment. Rather, he blames the Israelites for his punishment. “But the Eternal was angry with me on your account and would not listen to me” (Dt. 3:26)

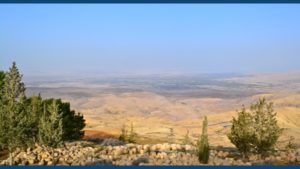

In what seems like a further punishment, God commanded Moses to ascend a mountain and see the land which he would never enter. This part of the punishment seems as if God inflicts a measure of cruelty upon Moses. Perhaps that is why Rabbi Bachya ben Asher (Translation by Eliyahu Munk, 1998) writes in his commentary “Our sages in the Midrash and the Talmud (Shemot Rabbah 3,19) are on record that originally ‘the sela (rock) dripped blood’ i.e. that when Moses hit the rock it first produced blood instead of water.” Even the rock felt the heaviness of the punishment that would rest upon Moses.

Is God’s showing Moses the land he would not enter in fact cruel or even a punishment? He may not actually enter the land but, Moses gets to see the reality of the land that would be the Israelite’s. Is it because he is the greatest of all the prophets as it says: “Never again did there arise in Israel a prophet like Moses.” (Dt. 34:10)

As we look at the prophets and leaders in the Tanakh, not a single one sees the actual fulfillment of his/her prophecy (although a case may be made that Deborah did. See Judges 4 and 5.) How much the more so for us?

No one ever gets to finish the task. Reality teaches us that in every aspect of life, as soon as we reach what we think is the “Promised Land” the next step looms before us, and ultimately falls to our successors. Moses does not lead the people into Canaan, that is Joshua’s task. Joshua does not finish the settlement of the land, each of the Judges moves that process forward. David does not get to build God’s Temple in Jerusalem, that is Solomon’s to build. The list is endless.

This is true in our own lives, especially in our congregations. In fact, we in the Liberal community understand this phenomenon and encourage it. Our synagogue leaders, lay and professional, work to fulfill their visions of the perfect congregation. We adapt our practice. We modify our liturgies to make them relevant to our generation. We derive new interpretations that resonate within us. We understand that among our 1200 WUPJ congregations, spread throughout 50 countries, we have sculpted our Judaism for who we are and where we live.

Their term expires or their contract ends and the next “generation crosses the Jordan.” Those leaders move on and the next “generation” works to “settle the land.” The new leaders change, update, modify, and reinterpret for their generation. The progression moves forward on and on through the generations. The earlier leadership never seeing the physical goal, as Moses got to, albeit from afar.

As Progressive Jews, we understand another important lesson. We stand on the shoulders of those who preceded us. We have not abandoned the Judaism of our ancestors as we have changed and moved forward in time. Rather, we openly acknowledge that we stand upon their shoulders. Without what they taught and practiced, we would be creating our Judaism ex nihilo.

Our predecessors taught in the Talmud, Menachot 29b that when Moses ascended to heaven, God told him that a scholar would be born far in the future named Rabbi Akiva. Moses asks: “Ruler of the Universe, show this Rabbi Akiva to me. God replied turn around.” Moses found himself in Rabbi Akiva’s classroom “and did not understand what they were saying. When Rabbi Akiva arrived at the discussion of one matter, his students said to him: My teacher, from where do you derive this? Rabbi Akiva said to them: It is a halakha transmitted to Moses from Sinai. when Moses heard this, his mind was put at ease, as this too was part of the Torah that he was to receive.” (quoted text from www.sefaria.org)

Like Moses, our ancestors may not recognize our Progressive Judaism. Like Rabbi Akiva, we understand that we could not have our Judaism with out theirs. When we pass on our leadership to the next generation and are like Moses, not recognizing the Judaism they create, may our successors be like Rabbi Akiva and us. May the understand that they stand upon our shoulders and the shoulders of all those who come before us.

Shabbat Shalom.

———————————-

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ).