Imagine Abraham’s surprise! There he was, minding his own business, resting in his tent in the hills near Hebron. Suddenly, God appears to Abraham. Without warning and without explanation. Looking up, Abraham sees the dust rising in the distance, and soon a group of strangers approach his tent. Without hesitation, Abraham leaps to his feet, ignoring God, and ignoring the pain he feels from his recent entry into the covenant with God through circumcision, and instead turns to these visitors.

Noah was destined to be neither the father of the Jewish people nor the founder of our faith. Though the most righteous one in his corrupt generation, he failed to reach out and save human lives besides those of his family. Thus, the Rabbis who were aware of Noah’s disturbing limitations in the terse yet […]

The Torah portion this week is titled Noach. It covers from the time of Noach, through the narrative of the Tower of Babel and then it lists a series of names ending up with Abraham and Sarah. The greatest amount of space in this section, in fact several chapters are devoted to Noach and the Flood. I would suggest that there are two matters that are take home lessons in these multiple verses.

The first point is that when Noach is introduced to us he is termed “a righteous man” – in Hebrew a tzadiq. The Torah then says, he was blameless in his age.

Hundreds of years later, after the close of the Bible’s covers, the early rabbis pondered what this meant. Yes, he was righteous. Yet, they ask, was he truly righteous, or was he righteous only in comparison to his age? In short, would he be considered righteous today, or was he only the best example of a pretty miserable lot of people? Was the bar set so low that he looked good, or even very good, but his contemporaries were so awful that his righteousness did not set a very high standard?

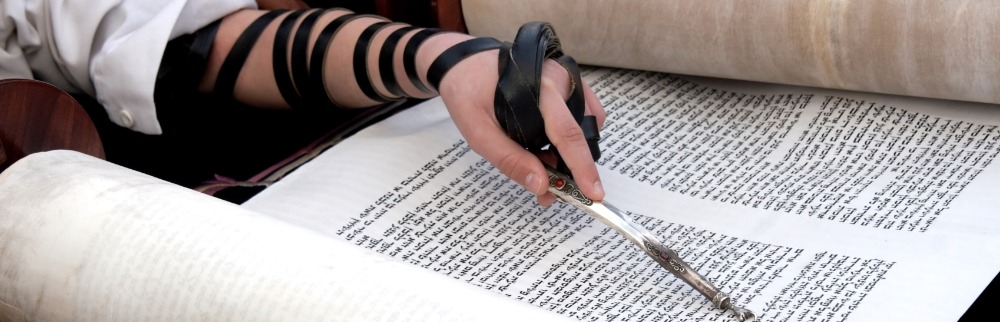

One aspect of Torah study that I love is when our sages see something in the grammar of the Hebrew of the Torah itself that stands out to them as unusual. It might be a small and seemingly insignificant or trivial matter to the Hebrew reader like a vowel or letter that appears out of place in a sentence. It would not even get our attention in the English translation. Yet, for the rabbis who have laser-like focus on the Hebrew text, they immediately presume that there are no accidents of grammar. They always believe that there is a hidden meaning behind every letter and vowel in the Torah. The challenge is to figure out what is the hidden meaning.

After the days of Awe – the days of judgment and blot, forgiveness and repentance – come the days of celebration, the days of joy and of praise. After fasting, we rejoice in Sukkot as the Torah instructs us in Deuteronomy 16:15:

Seven days shall you keep a feast to the Lord your God in the place which the Lord shall choose; because the Lord your God shall bless you in all you increase, and in all the work of your hands, and you shall be altogether joyful…

The feast of Sukkot, of all our holidays, is the one is characterized by the idea of universalism.

As we approach Yom Kippur we say, G’mar hatimah tova… May it be a good ending, as we leave Yamim Noraim and begin the journey of a new year… But life teaches us new meanings to old words and sometimes our defects may teach us with our blessings cannot. Late one eve at the end […]

Then the telephone rang, and I heard the most heart-breaking news: the night before receiving some important examination results, the child of an old school friend had just taken their own life. When disease or adversity threaten our lives, we humans fight with such fortitude and tenacity. How could life have become so dreadful that this young person felt that the only way to deal with the pain was to make a permanent exit? How could they feel so alone and unheard? How could they choose death?

In Ki Tavo, we join the Israelites on a journey towards a special location, to be chosen by God, in the land in which they were going to settle. They would bring a vat filled with the first fruits to the Cohen on that spot, to be laid before the altar of God, and recite a declaration, seen in verse 5 of our sidra, in words that might be familiar to you, “arami oved avi…a wandering Aramean was my father.” We also recite those words at the beginning of the maggid, the lengthy section of the haggadah, when we sort of tell the story of pesach.

Parashat Ki Teitzei contains the most laws of any Torah portion, seventy-four, more than one tenth of all the laws in the Torah, but it is also a good reminder that for the development of the halachah, Biblical law was just a building block. For example, the somewhat confusing law, that one must place a parapet on one’s roof; (Deuteronomy 22:8) not only becomes the basis of the Jewish equivalent to OSHA (Occupational Health and Safety Administration) regulations, but also is used by more contemporary authorities to develop a Jewish legal objection to second hand smoke. (OU Israel, Aliyah-by-Aliyah Parashat Ki Teitzei).

“You Shall appoint judges and public officials for your tribes, in all the settlements that Adonai Your God is giving to you, and they shall govern the people with due justice (Mishpat Tzedek) You shall not judge unfairly, you shall show no partiality you shall not take bribes for bribes blind the eye of the discerning and upset the plea of the Just. “Tzedek Tzedek Tirdof”, Justice, Justice you shall pursue that you may thrive and occupy the land that Adonai your God is giving you.” (Deuteronomy 16:18-20)