Parshat Balak was the Torah portion read on my first Shabbat as rabbi of the congregation I would go on to serve for 35 years. I observed then that there must be something instructive — and maybe cautionary — to be gleaned from the coincidence of assuming this new pulpit on the Shabbat when we read a Torah portion that prominently features a talking ass. My new congregation laughed – with me rather than at me, thankfully. But the truth is, that among the insights found in this complicated Torah portion, is this: what we say reveals a great deal about who we are.

In this week’s Torah portion, Chukkat, we read: “The community was without water and they joined against Moses and Aaron”. This reaction from the community is not a big surprise. After Miriam’s death earlier in the chapter, finding water became one of the greatest concerns for the people of Israel.

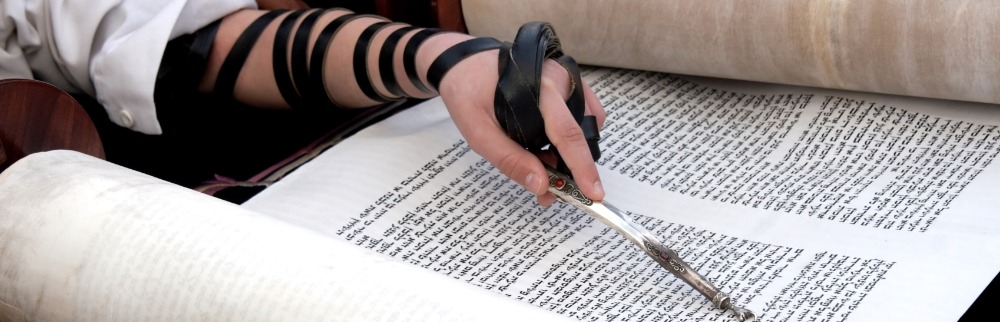

“And the LORD said unto Aaron: ‘Thou shalt have no inheritance in their land, neither shalt thou have any portion among them; I am thy portion and thine inheritance among the children of Israel.” — Numbers 18:20

You are set aside, for a special purpose and destiny. Your “portion” now and forever more shall be the Eternal. Which really means your portion is 100 percent rooted in your faith that God and the people will care for you and your family.

Twelve men, representative from each tribe, have been sent to reconnoitre the land of Israel, and they come back with the same report but with two different conclusions. The land is very good and fertile, but the inhabitants are strong. Ten believe that it would be impossible to take the land and it is better not to try, two insist that trusting in God and refusal to be afraid will mean that they will indeed succeed.

I am an avid reader. I enjoy most genres and love to get suggestions from my colleagues and friends. I will start a novel just because a trusted friend recommended it, without researching its topic or other reviews. I also enjoy rereading the classics. Occasionally, when rereading a story, an image or a plot twist will seem different or raise a conflict which feel new to me. When I have that reaction to the new information, I push myself to continue and figure out why.

Finding good leaders for our congregations is an ongoing challenge, one that exists whether you are in Alaska or New Zealand. This week’s portion offers us guidance in finding the right leaders, in the story of two very minor characters.

The rabbinic conference in Columbus, Ohio 1937 must have been fraught and tense – the Reform movement in the United States was on the edge of redefining its relationship to a personal God and to Israel – and some rabbis felt that the core values of Reform Judaism were on the chopping block.

With Pesach the rain in Israel generally ends. But this past week we had quite a storm! The Hebrew language has multiple words for rain. Geshem is the most general word. Yoreh refers to the early rain. And malkosh the late rain. This week’s Torah portion, Behukotai, is one of many traditional Jewish sources that views rain as a reward to the Jewish people for obeying the commandments:

Virtually, the entire book of Leviticus imagines God speaking to Moses. It is all instruction and no action. One significant departure into narrative is a striking little tale begun in Chapters 9 and 10, the ordination of Aaron and his four sons as priests (kohanim) for the people Israel, and the disastrous action of two of the sons that lead to their fiery death. The story concludes six chapters later, with the Torah portion, Acharei Mot. Depicted here—almost hidden among the thicket of priestly laws and regulations—is one of the most dramatic scenes in Torah: the first Day of Atonement.

The double-portion of Tazria-Metzora (Lev 12:1 – 15:33) presents a series of ritual purity instructions for Israelite priests, starting with procedures for women who have recently given birth, and shifting to the rules priests must follow to identify, quarantine, inspect, and ultimately, readmit to the community people with an ancient skin disease called tzara’at. In my first years working with b’nai mitzvah students, I repeatedly witnessed the disappointment of kids upon learning that Tazria-Metzora was their parashah. I would try to reassure them that, with help, they really would be able to find something relevant to their lives within these verses. The cultural distance, confusion, and even revulsion that many experience when encountering these parts of Leviticus are tough to overcome. And yet, with some cultural translation and an open mind, Leviticus can teach us a lot.